|

ANNE B. REAL:

A CINEMATIC HIP-HOP TRIBUTE

TO ANNE FRANK

“Who owns Anne Frank?” Cynthia Ozick asked, in a provocative essay she published in the NEW YORKER magazine in 1997. It’s easy to agree with Ozick’s attack on those who strip Anne Frank of her Jewish identity and make her into a “universal” cultural commodity. Nevertheless, no one can ignore the fact that Anne’s diary has been translated into almost every common language, and millions of copies are treasured, especially by young women, around the world. Creative artists of every background will therefore continue to find their own inspiration in Anne’s words with surprising results, the most recent of which is a wonderful new film called

ANNE B. REAL.

A teenage girl of Afro-Caribbean heritage named Cynthia Gimenez lives in a cramped Manhattan apartment on the edge of Spanish Harlem. Her mother and grandmother speak minimal English. Her older sister is an unwed mother living on welfare. Her older brother is a drug-dealing junkie. In the course of the film, Cynthia faces chaos and betrayal. One of her buddies is deliberately murdered, while another of her loved ones is accidentally shot. She runs from the police at one point, and to them at another. But through it all, Cynthia has a secret friend: Anne Frank.

In a flashback scene early in the film, Cynthia’s now-dead father gives his young daughter a dog-eared copy of THE DIARY OF ANNE FRANK, and for the rest of the film Anne’s words, read verbatim by Cynthia, provide both her solace and her inspiration. Cynthia buys herself a plaid notebook that looks very much like Anne’s original, and she retreats to her corner, like Anne did, to record her private thoughts. “All children must look after their own upbringing,” she reads, and from these words she understands that she can either blame her surroundings and give up, or take responsibility for her own future.

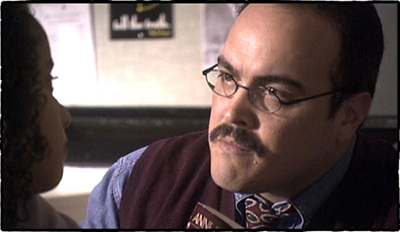

Cynthia’s father (David Zayas) gives his young daughter

a copy of THE DIARY OF ANNE FRANK.

(Photo by Suzynne Recio)

She finds out that her brother is selling her poems to a rapper named Deuce who has been performing them and recording them and claiming them as his own. But with Anne’s voice in her head, Cynthia finds her courage, and by the end of the film she has transformed herself into an artist named “Anne B. Real.”

High school student Cynthia Gimenez (Janice Richardson)

transforms herself into rap artist Anne B. Real.

(Photo by Suzynne Recio)

ANNE B.

REAL won major awards at several film festivals and was nominated for two Independent Spirit Awards this year (director Lisa France was nominated for a John Cassavetes Award for Best Feature made for under $500,000, and Janice Richardson, who plays Cynthia, was nominated for Best Debut Performance), but the film never received a theatrical release. However it is now available on DVD, and it’s definitely worth tracking down.

Sensitive to the raw language which pervades hip-hop culture, Ms. France insisted that all her actors respect her intention to make a PG-rated film before they signed on. In an exclusive interview, Ms. France told the WORLD JEWISH DIGEST she had two reasons for this requirement. First she wanted the film to be suitable for everyone, including Anne’s legions of young readers: “Urban family entertainment is rare. We wanted to make a film that an 8-year old and a 90-year old could watch together and we would not feel embarrassed or uncomfortable.”

The second motivation was her respect for Anne Frank’s legacy. When Antonio Macia, who plays one of Cynthia’s teachers in the film, wrote the original screenplay, he paraphrased Anne’s words. Once the film was a go, however, producer Luis Moro contacted the Anne Frank Foundation in Switzerland and received permission to quote extensively from the actual text. According to Ms. France, Bernd Elias, one of Anne’s last surviving relatives and the President of the Foundation, was extremely supportive.

Would Cynthia Ozick approve of a film that explicitly compares Anne’s Amsterdam annex to Cynthia’s Amsterdam Avenue apartment? Probably not. But the important point is that Anne gave us specific, hard-won insights into the realities of the world she knew firsthand, and so does Cynthia. Anne was never able to tell us about her experiences in Westerbork, Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen, so parents and teachers share responsibility for explaining exactly how and why Anne died. But we don’t honor her life if we only focus on her death.

Like her heroine, Ms. France finds an artistic imperative in Anne’s words. “If we’re ever going to have peace in this world, we have to continue to make stories that join cultures,” she said. I think Anne Frank, who pasted Hollywood photos around her bed and dreamed that her words would make her immortal, would agree.

If you look on the Anne Frank Foundation website, you will find these words: “It was a particular wish of the founder [Otto Frank] that the AFF should contribute to better understanding between different religions, to serve the cause of peace between people and to encourage international contacts between the young.” No wonder then that AFF members told Ms. France that when they finally saw her film, they were so moved that they watched it twice in a row.

© Jan Lisa Huttner (4/1/04)

|