|

Charles Guggenheim directing

BERGA: Soldiers of Another War |

BERGA

&

the legacy of

Charles

Guggenheim

|

Sixty years ago, almost to the day, American war-crimes investigators fanned out around the little German town of Berga on Elster in search of bodies. They were trying to find out exactly what had happened to a small contingent of GI’s removed from Stalag IX B in the waning days of World War II. The evidence was soon overwhelming: in violation of the Geneva Conventions, American prisoners of war had been worked to exhaustion in a German concentration camp, and then forced on a death march when Allied armies closed in on them.

American war crimes investigators exhume

the body of a GI who died on the death march.

Photo courtesy of Grace Guggenheim.

True to their bureaucratic imperative to the bitter end, the Nazis provided a written record of the 350 men transported to Berga. This list, stored by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), begins with the names “Slotkin” and

“Feinberg.”

“Nearly all of the first eighty names are recognizably Jewish,” writes Roger Cohen, author of the new book,

SOLDIERS AND SLAVES: AMERICAN POW’S TRAPPED BY THE NAZIS’ FINAL

GAMBLE. The bodies of the dead were exhumed and autopsied, and the bodies of the (barely) living were dispatched to stateside hospitals. The survivors of the Berga concentration camp were interviewed, discharged, and sent home to their families as quickly as possible. According to Cohen, the Army stonewalled requests for specific information from relatives of the dead, and all too soon, documentation was locked away for decades in NARA’s classified archives.

“But,” observes Cohen, “the truth will out in the end.” In the case of Berga, this process began when Jewish-American filmmaker Charles Guggenheim started working on a documentary film about Berga in 1995. His interest was personal; he was a member of one of the units captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. Hospitalized stateside with a severe infection when his unit shipped out, he’d spent 50 years brooding about the fate of his comrades-in-arms. The question became an urgent one for him: He died of pancreatic cancer soon after his film

BERGA: SOLDIERS OF ANOTHER WAR was released in 2003.

BERGA is an extremely powerful film, using original footage blended with recreated scenes. The soldiers, filmed as “talking heads,” are seen as old men until the very end, when Guggenheim shows them reunited with their families in post-war photographs. They tell the story in their own words, and when explanations are required, Guggenheim does the narration himself with spare simplicity. There are no experts or extraneous voices; every word comes from a primary source.

Bob Rudnick (l) & Gerald Daum (r)

two Jewish boys from Brooklyn

who survived the Berga camp.

Photo courtesy of Grace Guggenheim.

SOLDIERS AND

SLAVES, on the other hand, is deeply flawed. Cohen is an experienced journalist who served as foreign editor of The New York Times and still writes a weekly column for the International Herald Tribune, but his book is indulgent, embellishing the life stories of participants rather than increasing our knowledge of their ordeal through fact-based reporting.

SOLDIERS AND

SLAVES

is dedicated to the memory of Charles Guggenheim, and explicitly “inspired by”

BERGA, but it sticks too close to Guggenheim’s soldiers, and fails to make appropriate use of the NARA data which it references only tangentially.

Cohen means to honor Guggenheim, but fails to do so by not addressing any of the hard questions

BERGA

raises. For instance, who were the American men interned in Berga? Both Guggenheim and Cohen tell us that the Nazis started their list with every soldier who identified himself as a Jew under interrogation. Then they added the men who had “Jewish-sounding names,” even if they said they were Catholic or Protestant; then they added the men who “looked Jewish”; then they added “troublemakers,” until finally they reached the number of workers they were asked to provide by their superiors.

But all the GI’s were wearing dog tags which identified them by religion. Sixty years on, we now know most of what the American government knew about the Holocaust at that time. By 1944, when most of these soldiers shipped out, didn’t anyone in the U.S. military question the practice of stamping H’s (for Hebrew) on the dog tags of Jewish men bound for Europe? Didn’t anyone alert the officers, or instruct the Jewish soldiers on how to identify themselves if captured? If not, why not?

Maybe Cohen could find nothing relevant in the NARA archives, and no one still alive could provide further illumination, but there’s no indication in his book that Cohen even tried to dig into these obvious questions. Berga is significant because it’s an American story, but Cohen loses his nerve, lets the American government off the hook, and starts shooting fish in a barrel. (Reporting new Nazi war-crimes, in 2005, is just too easy.)

Also missing from Cohen’s book is a thorough analysis of the troubling issue of compensation. The American government denied disability claims submitted by Berga survivors immediately after the war, but suddenly, in the late 1990’s (in other words, after Guggenheim began working on his film), survivors started receiving checks from the German government through the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. When and why was a lawyer retained, and exactly who retained him? What discussions led to the decision to take this action? Cohen doesn’t say; he devotes a mere two paragraphs to all of the compensation issues.

Beyond the importance of the POW story in itself, there’s another reason to get the DVD edition of

BERGA: to celebrate the life achievements of a great Jewish-American artist who won four Oscars and was nominated for many more. In addition to the film, still broadcast on PBS at regular intervals, the DVD contains two bonus features: an hour-long interview with Guggenheim and a compilation of snippets from some of his best work.

Guggenheim loved architecture and expressly admired men who knew how to work with their hands. Putting the pieces together, the DVD shows that it took the creator of a great documentary about the Gateway Arch (MONUMENT TO THE DREAM) to reveal the secrets of the Berga tunnels. From the heights of idealism to the depths of degradation, Charles Guggenheim captured it all.

|

|

|

© Jan Lisa Huttner (7/1/05)

FF2 ADDENDUM

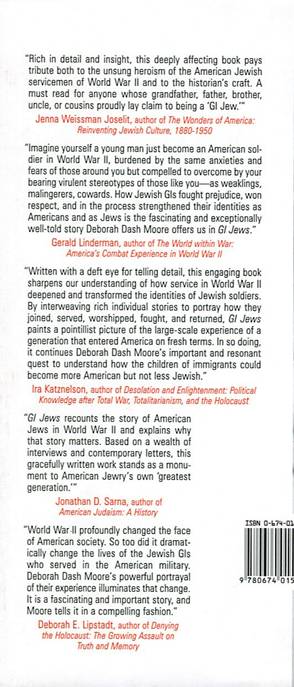

A much better book on this general topic is Deborah Dash Moore’s

GI

JEWS, released last August. Although she only devotes one page explicitly to Berga, Moore’s book provides both a context for understanding the situation of Jewish-American GI’s in World War II, as well as acute observations on the consequences of their service, not only for them as individuals, but also for the nation they served (the United States) as well as the nation they helped to create through their advocacy and financial support

(Israel).

Click

here to order

|

|

|

In his 6/12/05 review of GI

JEWS in the CHICAGO TRIBUNE, Columbia University journalism professor Samuel G. Freedman wrote: …One of the most distinguished historians of contemporary American Jewry, Moore can hardly be accused of sentimentalizing war. She teaches at Vassar College, which shares nothing with West Point except the Hudson River Valley, and she made her name with TO THE GOLDEN CITIES, a fine book about Jews in the postwar promised lands of Miami and Los Angeles. But she is also her father's daughter, and her father, Martin Dash, was a Brooklyn boy who served as an officer on the destroyer USS McCormick. Moore has built her trenchant and fluent book largely around the testimonies of Dash and 14 contemporaries. Some were Zionists, some were yeshiva students, some were Popular Front radicals, and virtually all had spent their prewar lives in insular, urban, Jewish neighborhoods. So when they went to war, they met gentiles and gentiles met them with an unprecedented intensity and mutual dependence. As Moore deftly weaves a narrative from the varied experiences of her informants--tracking them from Hitler's invasion of Poland in 1939 to battlefield victory and the liberation of the death camps in 1945--she refuses to merely celebrate. Her book includes instances of anti-Semitism in boot camp here and on the fronts overseas. In one especially searing moment, a Jewish chaplain is excluded from an ecumenical memorial service after the battle for Iwo Jima because he is an outspoken foe of racial segregation in the American military. Such unclouded vision makes Moore all the more credible in describing the more-common process of Jews proving their mettle to gentiles and securing their place in a more-tolerant postwar America. The very concept of a Judeo-Christian tradition, Moore points out, was a creation of World War II. This "civil religion for American democracy," as she aptly calls it, had its genesis in the widely reported deaths of Jewish, Catholic and Protestant chaplains when their transport ship was sunk by German U-boats in early 1943. With the revelation of the Final Solution, America could no longer morally sustain its own brand of anti-Jewish discrimination--the bias in housing, social clubs, higher education and so forth that were routine in the prewar decades. Impediments fell, and American Jews advanced. Returning Jewish veterans became "agents of a shift in the legitimization of American Jewish identity, one that would deepen the sense that Jews were at home in America," Moores writes of the GIs. "Belief in American exceptionalism was apparently being rewarded; things were different over here." She continues several pages later: "Standing up for oneself as a Jew turned out to be the American thing to do. Military service strengthened Jewishness in part by changing its meaning." Beyond the historical importance of Dash’s book, it has profound implications for the future. In Freedman’s words: …[GI

JEWS] implicitly raises a sobering question for American Jews… Like other highly educated and highly affluent groups, Jews began detaching from the military thanks to draft deferments for college students in the Vietnam War era, and today they enlist in the all-volunteer Army at less than half their proportion in the population. Something precious is being taken for granted, and potentially lost, in that disconnection… In his WASHINGTON POST survey of recent books on World War II (published on 6/5/05), Kenneth M. Pollack is also full of praise: The great surprise of the season in World War II books is Deborah Dash Moore's wonderful

GI

JEWS: HOW WORLD WAR II CHANGED A

GENERATION. Moore is a professor, the book is an academic study of how one small segment of the American population dealt with the war, it was published by an academic press and the endnotes are nearly a fifth as long as the story itself -- none of which promises an enjoyable read. But it is an enjoyable read. Moore, a Vassar professor, writes well and knows how to tell a story -- sins that some faculty committee will no doubt punish her for someday. She has an eye for interesting characters and for what makes them interesting. One of those characters, in fact, is her father, and others are old friends of his; yet she keeps her own feelings about him and them out of it, which allows them to live again in her pages as the young men gone for soldiers they once were. She keeps up a lively pace and intersperses

evocative vignettes with insightful analysis of what these Jewish troops' experiences meant to them, their families, their communities and the nation as a whole. The book's biggest draw, however, is the larger themes that Moore gracefully weaves throughout. The most important of these are echoed in her apt subtitle, "How World War II Changed a Generation."

GI

JEWS is a vital corollary to the work of Tom Brokaw and others who have justifiably lauded America's "Greatest Generation." Moore's most important theme is that the greatest generation was not born that way but forged -- something that, to be fair, Brokaw himself has acknowledged. Its members did not win World War II because they were the greatest generation, but they became the greatest generation because of what they went through during the war. Although Moore focuses on American Jews, the experiences she describes were similar, if not identical, for virtually every other ethnic group in the country, and indeed for most Americans. For postwar generations, her book reveals how the experience of the war changed the generation that fought it and why it helped launch the civil rights movement, the Great Society and America's rise to global predominance. GI Jews should not be missed by anyone with an interest in World War II or the history of the American people.

FINAL FF2

NOTE:

This article is a slightly expanded version

of the reviews originally published

in the July 2005 edition of the

WORLD

JEWISH DIGEST

(Volume 2 Number 10)

& is posted here with their permission.

For WJD subscription information:

Call 312.332.4172 extension 42

or

Fax 312.332.2119

|