Special Thoughts for FILMS FOR TWO®

by Alan Waldman

The late Elia Kazan was one of Broadway’s most honored directors, a top nurturer of acting talent, and the helmer of beloved movies that won 22 Academy Awards and 40 more Oscar nominations. Over time, however, Kazan became a pariah who was widely despised for having ruined the lives of eight former friends—primarily to preserve his own earning power—by revealing their names to the fanatical, red-hunting House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). When he was 89, Martin Scorsese and Robert DeNiro presented Kazan with a controversial lifetime achievement Oscar, while hundreds of ceremony attendees—including Nick Nolte and Ed Harris—refused to stand or applaud, and a large, angry crowd protested outside.

At Kazan’s death, on September 28, 2003, Karl Malden (who’d won a Best Supporting Actor Oscar 51 years previously for Elia’s classic film A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE) declared: “I idolize him. He was one of the best directors I've ever worked with in theater and films.” Two-time Oscar winning actor-director Warren Beatty once said of Kazan: “He's a magnificent machine in filmmaking, regardless of what your feelings might be about him politically.” (Beatty and his wife Annette Benning were among those who gave Kazan a standing ovation on Oscar night.)

Kazan was a pioneering stage and screen director in the 1940s and 1950s. He helped launch a revolution in naturalistic, psychologically–rooted screen acting while bringing to life startling plays and movies that questioned societal norms on important social questions such as racism, anti-Semitism, public corruption, alcoholism and misuse of the media. His directorial style combined the seemingly contradictory elements of naturalism and high theatricality.

Between 1945 and 1976, he directed 19 movies, including the classics EAST OF EDEN, A

FACE IN THE CROWD, GENTLEMAN’S AGREEMENT,

ON THE WATERFRONT, A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, A TREE GROWS IN BROOKLYN, and

WILD RIVER. He also staged five great, Pulitzer-prize winning plays (and earned Best Director Tony Awards for three of them): CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF, DEATH OF A SALESMAN, J.B., THE SKIN OF OUR TEETH, and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE.

Kazan was renowned as the top “actors’ director” of his generation, explosively launching the careers of unknowns Marlon Brando and James Dean, and guiding outstanding performances by Mongomery Clift, Robert De Niro, Jack Nicholson, Lee Remick, Eva Marie Saint, Jo Van Fleet, Natalie Wood and many others—nine of which resulted in acting Oscars.

Kazan himself won the Best Director Oscar for GENTLEMAN’S AGREEMENT and

ON THE WATERFRONT (both of which also took Best Picture statuettes), and accumulated nine Venice Film Festival awards, four Golden Globes, three New York Film Critics’ Best Director prizes, two Danish Bodils, the DGA lifetime achievement award, and film honors in Germany, France, Spain and Turkey.

“I’ve never seen a director who became as deeply and emotionally involved in a scene,” Marlon Brando wrote of Kazan. Actress Mildred Dunnock (BABY DOLL) observed: “Some directors regard actors as a necessary evil; others, as children to be handled, but Kazan treated an actor like an equal. Once he casts you, he makes you confident.”

An Anatolian Greek, he was born Elia Kazanjoglous in the Ottoman Empire city of Constantinople (now called Istanbul), on September 7, 1909. Four years later, his family moved to a Greek section of Harlem (in New York City), where Elia attended public schools. Later they

immigrated to suburban New Rochelle, NY. Father George Kazanjoglous expected Elia to go into the family rug business, but mother Athena encouraged the boy to make his own decisions.

While majoring in English at Williams College, Elia picked up the lifelong nickname “Gadg”—short for “gadget” (“Because I was small, compact and eccentric,” he subsequently explained). In his senior year, Kazan was deeply affected by Sergei Eisenstein’s masterpiece POTEMKIN, and after graduating cum laude, he did postgraduate drama study at Yale.

In 1932, Kazan married the first of his three wives, playwright Moly Day Thatcher, with whom he had four children. One son, Nicholas Kazan, wrote 12 screenplays (including

FRANCES and REVERSAL OF FORTUNE) produced three (including MATILDA and FALLEN) and directed two.

Gadg joined the legendary, left-leaning Group Theatre in Manhattan, in 1933, as an actor and assistant stage manager. There he worked in socially significant dramas alongside towering talents such as Clifford Odets, Lee Strasberg, Stella and Luther Adler, John Garfield, Lee J. Cobb and Howard Da Silva (many of whom were also called before HUAC in the ‘50s).

Kazan joined the American Communist Party in 1934 and performed in fellow Party member Odets’ plays WAITING FOR LEFTY, GOLDEN BOY and PARADISE LOST, although he preferred directing Group productions such as CASEY JONES and CAFÉ CROWN. He left the Party two years later, unhappy with both Stalin and the American Party’s influence on the Group’s direction.

In 1942, after the Group Theatre disbanded, Kazan earned recognition (and a New York Drama Critics’ Award) for directing Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer-pulling THE SKIN OF OUR TEETH. Gadg would go on to direct a dozen of America’s finest plays, penned by giants such as Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams and John Steinbeck, harvesting a slew of major drama awards in the process.

Williams once said that Kazan “approaches a play more critically than anyone I know, so you find yourself doing more revisions for him than for any other director.”

After directing Williams’ play A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE in 1947, however, Kazan began sending the playwright long letters requesting (and getting) substantial changes in his works—until Williams complained in 1955 that Kazan had usurped his authority as writer on CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF.

Kazan got into movies by assisting documentarian Ralph Steiner in the mid 1930s and acting in two Warner Bros. films. Darryl Zanuck signed him to a 20th Century Fox contract in 1944, and a year later he made his feature directing debut in A TREE GROWS IN BROOKLYN. That touching evocation of turn-of-the-century working-class tenement life won Oscars for stars James Dunn and Peggy Ann Garner.

In 1947, Group Theatre vets Kazan, Cheryl Crawford and Robert Lewis founded the Actor’s Studio, which taught Stanislavski’s “method acting” to a generation of titanic talents, including Marlon Brando, James Dean, Shelley Winters, Paul Newman, Robert De Niro, Ann Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman, Jane Fonda, Martin Sheen and Sidney

Poitier.

That same year, Kazan directed three movies. BOOMERANG, a multiple award-winning courtroom mystery, dealt with political corruption. SEA OF GRASS, a melodramatic adultery Western, starred Katherine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy. GENTLEMAN’S AGREEMENT, the most famous of the three, was considered a bold look at anti-Semitism; it starred Gregory Peck and featured Celeste Holm, who won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar.

Back on Broadway, Kazan directed Arthur Miller’s masterpiece DEATH OF A SALESMSAN, which one critic called “as exciting and devastating a theatrical blast as the nerves of modern playgoers can stand.”

Jeanne Crain, Ethel Waters and Ethel Barrymore were all nominated for Oscar’s in PINKY (1949), in which a light-skinned African American woman passed for white. Like GENTLEMAN’S AGREEMENT, it was considered a brave examination of racism at a time when such issues weren’t screened.

A year later, he let Zero Mostel and Jack Palance chew up the scenery in the plague-infected gangster drama PANIC IN THE STREETS, which won Oscars for screenwriters Edward and Edna

Anhalt.

Kazan made three of his next four films with his Actor’s Studio pupil and stage protégé Marlon Brando. A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951) launched Brando’s superstar career and won Oscars for his co-stars Vivien Leigh, Karl Malden and Kim Hunter; three of its 12 Academy Award nominations went to Brando, Kazan and screenwriter Tennessee Williams.

Brando was nominated again a year later for Kazan’s VIVA ZAPATA, as was screenwriter Steinbeck. Co-star Anthony Quinn won Best Supporting Actor. Brando once called Kazan an “arch-manipulator of actors’ feelings,” and during the filming of VIVA ZAPATA, Gadg apparently told Quinn that Brando was saying things about him behind his back—to intensify the conflict between their screen characters.

When HUAC first questioned Kazan, on January 14, 1952, he refused to "name names." Shortly thereafter, however, Fox president Spyros Skouras (and, according to some reports, J. Edgar Hoover) ordered Kazan to name names or say farewell to films. Gadg reappeared before the committee on April 10 and identified eight of his Group Theatre pals (who had been Communist Party members with him), along with some party functionaries. His testimony against playwright Clifford Odets, actresses Phoebe Brand and Paula Miller (Lee Strasberg's wife), actor John Garfield and others helped to destroy their careers. Although HUAC was unable to prove Garfield was a Communist, it blacklisted him anyway, and he died a year later, a broken man, at age 39.

While Sterling Hayden and other squealers later regretted their treachery, Kazan never apologized but continued to justify his behavior on moral grounds. He claimed that Communist activities represented “a dangerous and alien conspiracy” that needed to be exposed. He later wrote: “I'd hated the Communists for many years and didn't feel right about giving up my career to defend them… Within a year I'd stopped feeling guilty or even embarrassed about what I'd done… There's a normal sadness about hurting people, but I'd rather hurt them a little than hurt myself a lot.”

In his book NAMING NAMES, Victor Navasky, wrote: “Probably no single individual could have broken the blacklist in April 1952, and yet no person was in a better strategic position than Kazan, by virtue of his prestige and economic invulnerability, to mount a symbolic campaign against it, and by this example inspire hundreds of fence-sitters to come over to the opposition.”

One reason Kazan’s actions earned him a half-century of hatred was the widespread belief that he—unlike most others grilled by HUAC—could have saved his friends and still made a good living in the theater. On Broadway, where he was the single most popular director (earning over $400,000 in previous year), there was no blacklist.

Before Kazan’s unrepentant destruction of his colleagues, he and playwright Arthur Miller had been like brothers, but for the next decade they did not speak. Miller, who refused to name names before HUAC, later wrote, “He would have sacrificed me as well.”

Kazan’s next four films were also well regarded, but they began the long decline in his quality of his work. He won a Golden Globe for directing Carroll Baker as a strange, sex-avoiding Southern wife in BABY DOLL (1956). A

FACE IN THE

CROWD (1957) starred Andy Griffith as a malevolent huckster (allied with a fascist Senator) who becomes a massive media hero. Montgomery Clift stayed sober during much of the filming of

WILD RIVER

(1960), which was nominated for a Berlin Golden Bear. And the period romance SPLENDOR IN THE GRASS (1961) introduced teenage stars Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty.

Although he had continued to alternate film jobs with major Broadway successes for nearly two decades, Kazan abandoned both Broadway and the Actor’s Studio in 1962 for his first major failure: a disastrous two-year stint co-heading Gotham’s Lincoln Center Reparatory Company.

Gadg’s last hurrah (before his controversial 1999 Oscar) was earning Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay Oscar nominations for writing and directing AMERICA, AMERICA (1963), which chronicled his Greek immigrant uncle’s troubled voyage to the New World.

In the final 40 years of his life, Kazan wrote novels, directed three unsuccessful films (1969’s THE ARRANGEMENT, 1972’s THE VISITORS and 1976’s THE LAST TYCOON), wrote an autobiography in which he boasted of bedding Marilyn Monroe and many other screen-hungry starlets and married twice more—once to Barbara Loden, who played Monroe in Arthur Miller’s autobiographical play AFTER THE FALL.

The announcement that Kazan would receive a 1999 honorary Oscar evoked an explosion of outrage. Placards outside the ceremonies dubbed it the “Benedict Arnold Award.” Blacklisted writer Abraham Polonsky (BODY AND SOUL) opined: “I hope somebody shoots him. When he goes to Dante's last circle in hell, he'll sit right next to Judas.”

Although he was a brilliant, pioneering director, an important social commentator of the ‘40s and ‘50s and a great nurturer and teacher of talented performers, Elia Kazan will always be primarily known for betraying his friends—for money. I loved his best movies but reviled him as despicable sellout who lacked the character to ever admit he had done wrong.

Three years after testifying, Kazan declared: “I can get along all right with you disliking me. I do my work my way and don’t pay attention to the reaction.” And in his 1988 autobiography, ELIA KAZAN: A LIFE, he wrote: “Since talent is so often the scar tissue over a wound, perhaps I had more than most men. Study those you admire for what they've accomplished, and you may be able to identify the painful and costly events that made them despair for a time but that, in the end, they had to thank for the fortitude of spirit that made it possible for them to achieve what they

did.

|

ALAN WALDMAN’S SEVEN FAVORITE ELIA KAZAN FILMS: |

1. On the Waterfront (1954)

2. A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

3. East of Eden (1955)

4. Gentleman’s Agreement (1947)

5. A Face in the Crowd (1957)

6. Splendor in the Grass (1961)

7. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945) |

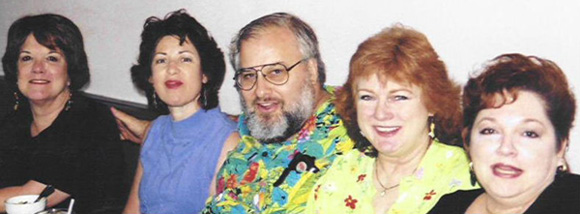

Writer Alan Waldman and four of his seven ex-wives, on the Cote

d’Azur.

Each July, whichever of his exes are not currently institutionalized gather

allowing Alan to visit his former money.

The 27th and oddest of Belarus fishmonger Farvel Friedberg’s 40-odd great-grandchildren, Alan Waldman is a notorious journalist, raconteur, seducer and poor credit risk. In the 19th Century, Alan’s great-uncle Fritz sold the same horse to one of Emperor Franz Josef’s generals three times. The tree from which Fritz Waldman was hanged can still be viewed in downtown

Chernovtzy, Moldova.

© Alan Waldman (10/26/03)

A FINAL NOTE FROM FILMS FOR TWO®

Please note that we began this website in 2000. Therefore, although we have seen most of the films Alan mentions in this article, most of them are not (yet) represented in our database. We thank Alan for his personal perspective on Elia Kazan’s remarkable career. Kazan was undeniably one of the giants of American cinema. For the record, our own all-time favorite Kazan film is

ON THE WATERFRONT, although Jan has always had a special fondness for

WILD RIVER as well.